Rediscovering some Aussie natives at Kingston Heath Golf Club

Words: William Watt

Photos: Mano Gonzales

Indigenous heathland species are being brought back to the inner city with the help of Melbourne’s most prestigious golf clubs.

“That’d be your club emblem right there,” said Pete Murray, pointing out to the management of Kingston Heath Golf Club a Common Heath plant perched on the bunker edge of their 12th fairway. The white Epacris Impressa that Pete had spotted was the sole survivor on the entire property, despite its suitability to the site and abundance in days gone by.

It also happens to be the state of Victoria’s floral emblem, all but forgotten in these parts until an Indigenous plant movement gained momentum throughout the golf courses in Melbourne’s famed Sandbelt. Pete, an ex-chef who discovered his true passion in agriculture, was brought into Kingston Heath five years ago to kick-start the revegetation of the heathland species that thrive in this sandy, well drained soil.

“I knew the plants existed because I did a lot of work experience with Kingston Council, and with an Indigenous nursery nearby, where I learned what plants were what. As soon as I saw them here I knew exactly what I had and how uncommon they are. They may not be endangered in Victoria, but in the city itself, in Melbourne, they’re nearly wiped out. So on a local level, they are endangered. Today, Kingston Heath and other Sandbelt golf courses have got a really good supply of those species. But you’d never really see them in a garden or anywhere else but a golf course.”

As well as the beautifully delicate Common Heath, now planted throughout the course and thriving, Pete identified a rare species of bush pea hiding in the undergrowth, and has encouraged its growth. This alongside a Guinea Flower, the local Heath Tea Tree (which resembles a blossom at certain times of year), and the intriguing Xanthorrhoea Minor – a trunkless grass tree, which grows down instead of up.

Melbourne's Sandbelt Heroes

Pete shares a good relationship with the rest of the groundskeeping crew, whose primary focus is on turf management and keeping the course in the sort of pristine condition expected of one of the world’s best. “Ha, they call me ‘the native bloke’. But some are genuinely interested in what I’m doing here and keen to learn more and help out. I’ve been given free rein of anything that isn’t directly golf related, and they know to stay out. I guess I’m a bit protective of some areas.”

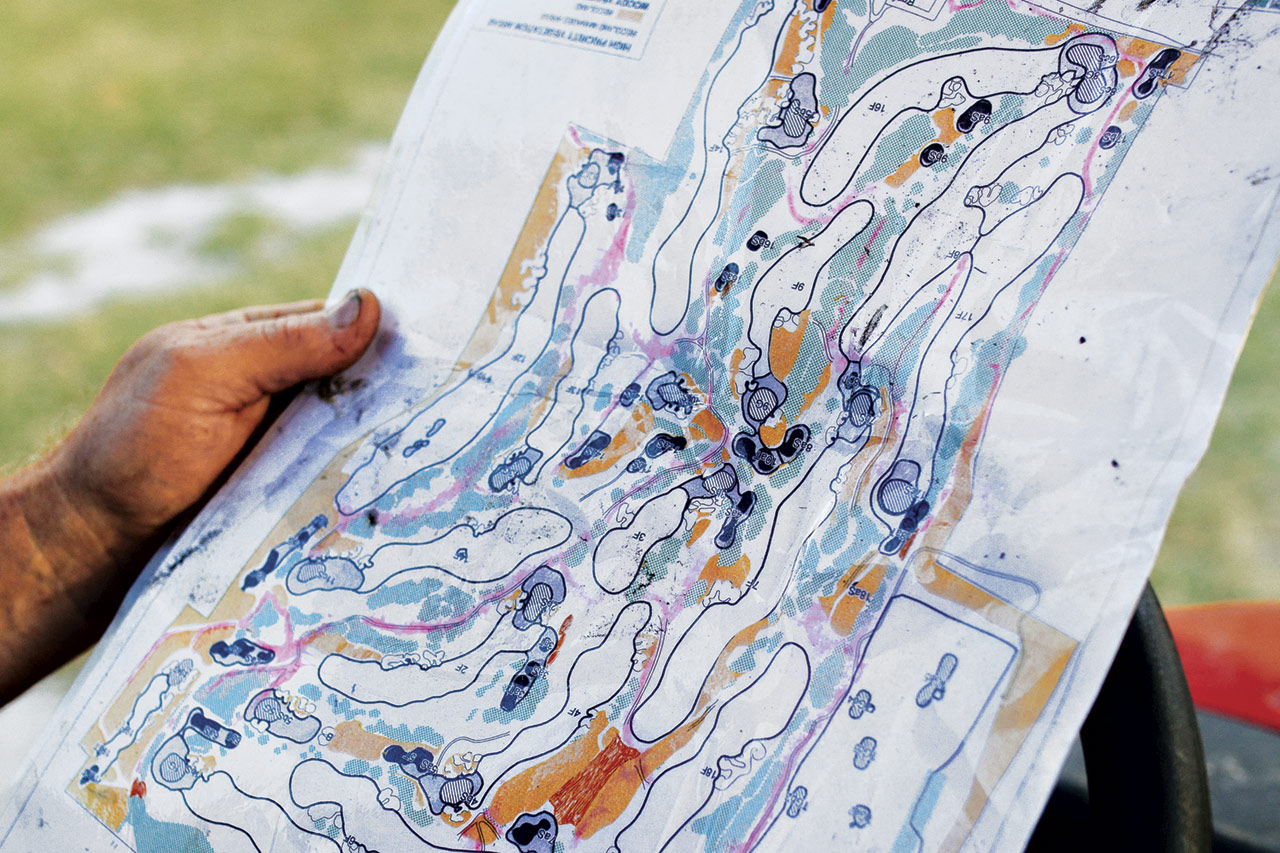

Growing some of these plants successfully isn’t as straightforward as one might think – detailed studies of the soil, water levels, wind exposure and drainage have identified four or five ‘vegetation clusters’ running throughout the course, and all must be planted accordingly for successful growth.

A positive effect of all this work, or perhaps an underlying goal, is that as well as creating a more authentic heathland experience for golfers, over time the vegetation on the course will require far less watering, making the course more sustainable and hardy.

It also provokes a wider conversation about the role of golf courses within a community. For inner city courses like those on the Melbourne Sandbelt, they hold a unique opportunity, and perhaps responsibility, to be a true representation of what the land was like before farming and urban sprawl paved over it. Certainly guys like Pete, who shudders at the site of some introduced species that still remain on site, will be pushing this message for years to come.